A Reference Architecture for Portability Threat Modeling

Among the many un- or under-researched questions in data portability, risk and threat issues loom large. We’d love to do some crunchy deep-dive threat modeling, but we’ll get lost in the weeds if we don’t focus.

“Data portability” collects together an interesting set of use cases. Not all of these are covered by the exact same architecture and functionality, or even involve the same parties. It’s all too easy to get lost in hypotheticals and lose track of how decisions fit together - like trying to solve two jigsaw puzzles at once but without committing to fit any pieces together.

However, there’s a combination of simple and real use cases, together with some obvious architectural choices, that can give us something to model threats upon. We need the use cases to motivate the architecture, but also because what attacks might really be threats depends heavily on use cases. And we need at least some architecture, not just the use cases, because it helps us see which threats are just hypothetical (some attacks can only work with an architecture we’re not likely to choose), and instead focus on threats that are more relevant.

As I try to describe a core usage model that will inform what kinds of threats are important, this will cause lots of “but-what-abouts” to arise: many readers are going to think of exceptions and extended use cases. Then, when I describe a reference architecture, the misgivings may be due to seeing other ways to solve problems or knowing what already exists. That’s OK. We don’t need to limit ourselves to the reference architecture or even just one architecture for all problems. The reference architecture will give us a reasonable option for considering threats, and then we can start to extend it or vary it – or compare to alternatives that might deal with different threats and be preferable for different use cases.

Quick Overview

First I want to make sure we’re on the same basic page, before spending a couple digital pages describing the details of a rhinoceros when you think I’m about to describe an elephant.

In one sentence, the core usage model can be summarized:

As a person with my data in a source service, I want to move it to a destination service by having the services handle transferring the data and making sure it lands correctly at the destination.”

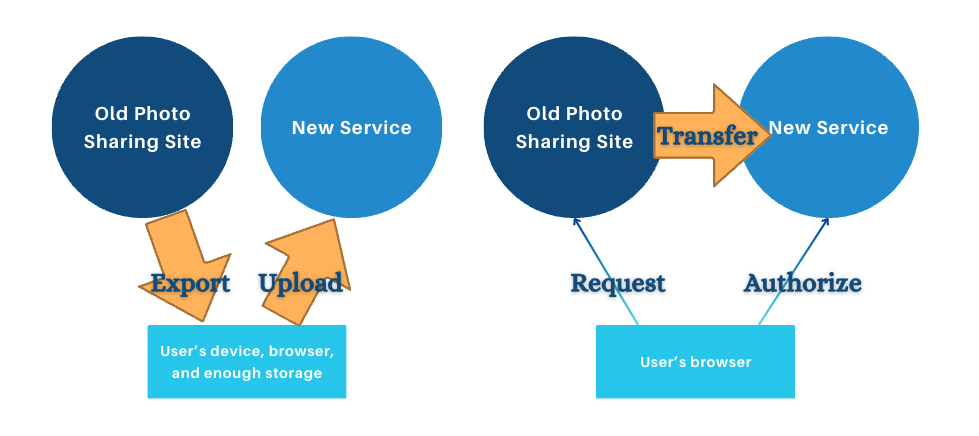

A key assumption here is that data travels directly between services, as opposed to the Export/Import approach where data is stored on a personal computer or online storage in between services.

Having services exchange data directly is key to practically exercising a right to data portability in cases where the data is in bulk quantity, requiring high bandwidth and storage capabilities, or the data is complicated enough to require agreement between the source and destination on a schema in order to transfer well.

The core interactions for server-to-server data portability look something like this:

- I must authorize a source service to access and send some data.

- I must authorize a destination service to accept that data on my behalf.

- After both authorizations are made, direct server-to-server transfer of data can begin.

This high-level description is missing a key decision, however. Does the authorization of the source service get sent to the destination so it can ask for data? Or does the authorization of the destination get sent to the source so that it can start sending? This is a question of who initiates the authorization request and who receives that authorization result.

| Source-initiated architecture | Destination-initiated architecture |

| On a data-transfer Web page owned by the source, the user will select a destination (e.g. from a drop-down list) and the source then requests the user to authorize the transfer to the destination. If successful, the destination provides the source with a way to prove that authorization to send data. | On a data-transfer Web page owned by the destination, the user will select a data source (e.g. from a drop-down list) and the destination then requests the user to authorize getting the data from the source. If successful, the source provides the destination with a way to prove that authorization to get data. |

As we’ll see later, and you can kind of tell from the mirrored language, these actually have a lot in common. Either system would work pretty well for a lot of use cases, and we don’t need to decide now.

Requirement Details

Now that we have the basic picture at a very high level, we need to characterize some real use cases in enough detail to make sure that the reference architecture works. In any interesting problem domain, there’s always quite a population of simple needs, complicated situations, and problems in between. When we draw a line and say which problems can be solved simply now, we’re often saying that the problems outside the line can be tackled later – and often by the same architecture with extra features.

I think the key things that characterize the simpler set of problems is that they are variations on a request from an individual person for a one-time data transfer of a known type of data. Let’s unpack these three pieces.

1. Person-centered

The core problem to solve is when a person makes a request involving that person’s own data.

When DTI talks about data portability we usually assume consumer and individual use cases. This arises in part from EU and US state regulations that emphasize individual data rights. Note that this centers not only the person but also **their data. **

The following use cases can be handled later or by different solutions:

- B2B use cases - any time data transfer occurs from business to business, without involvement or request of a user.

- B2B2B use cases, where the entity that wants to transfer data is itself a business. Data that is business oriented (retail data, business finance data, Human Resources data) is subject to different threats.

- Data that does not belong to the user might be transferable but has different privacy characteristics. For example, users might wish to select photos on a stock photo service and copy them somewhere else, but that has different characteristics than transferring my own private photos.

- Community data, even if it was contributed by the user, also has different privacy characteristics. For example, many knitters on Ravelry.com have contributed images and pattern information to a knitting pattern database, and those are now a communal resource.

What does remain in the core usage model includes both data about the user and data that the user_ contributed_. Those often overlap and both often require privacy, so we can conclude that privacy is a requirement of the core usage model and threats to privacy cannot be waved away.

Another facet of person-centered data portability is that we can start with the use cases where the person whose data is being transferred requested the transfer themselves. There are studies about the privacy and security considerations when two services exchange a user’s private data (Weiss, 2008), and those considerations are very different when the user didn’t request that exchange.

2. One-time

The one-time nature of the simplest data portability use cases is also an important simplification. It’s clear that there are some use cases that are satisfied with one-time data transfer, and while real-time ongoing data transfer functionality has fascinating and important uses, it is definitely more complicated. Ongoing transfer requires additional features ( like token lifetime limitations, token renewal, canceling, notifications) and those features introduce additional security considerations.

Repeated asynchronous data transfer use cases can also be deferred. As soon as we start thinking about repeated copying we will want to talk about features that are commonly part of backup or replication solutions, as well as token lifetimes and cancellation features as with real-time data transfer.

That’s not to say that the user can only request data transfer one time and never gets any other chances! It just means that our core architecture can focus on one transfer only, without relationship to past or future transfer requests – definitely a simplifying assumption.

Finally, we can solve the case where users can be notified about transfer status _in-band, _meaning they can learn about the completed transfer in the same place (likely a Web page, but possibly an app) where they kicked it off. Out-of-band notifications may be a complication to the threat model.

3. Known Data Types

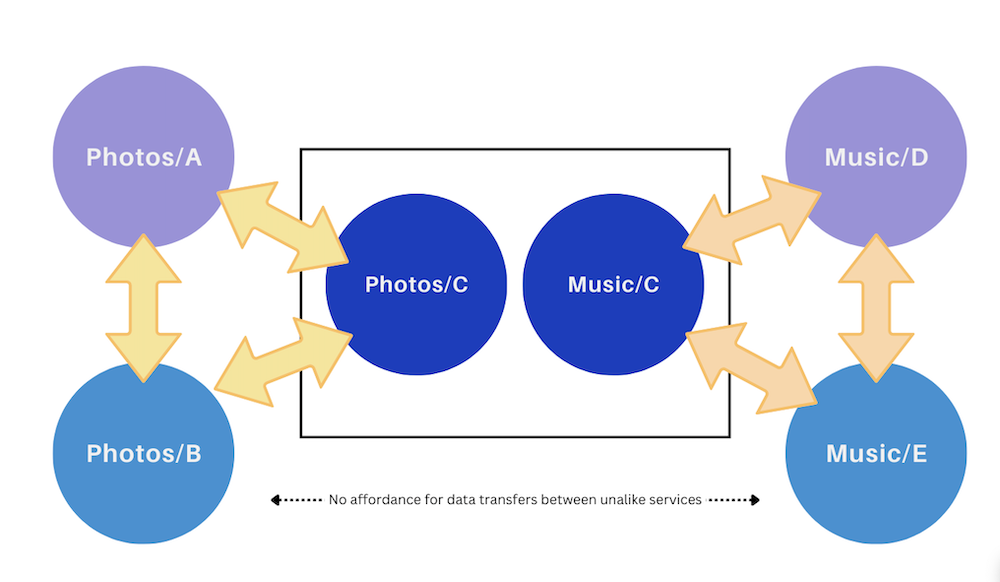

One of the most obvious and simple use cases is when a user asks to transfer their personal photo collection from one service to another photo service. The same architecture can probably be used when the user asks to transfer their music playlists from one music service to another music service. If we use the same architecture for both, does that mean we’re going to have a photo server start to send photos to music streaming servers, or that a music streaming server starts to send music playlists to newsletter hosting sites? No - that’s the difference between general-purpose and universal solutions_. _A general-purpose solution can be re-used, without requiring each service to handle the universe of possible data types.

Even though C hosts both music and photos, like only transfers to like

This will be a simplifying choice to both our architecture and to mitigating threats. Since a photo destination knows to expect photo data, it can check to see if the data is legitimately photos. The destination can reject data that it would not normally host. Nobody is going to require photo services to accept virus code packages and host them where only photos are supposed to be hosted.

We also don’t have to worry about the destination receiving a never-ending stream of binary data in a denial-of-service attack, because we allow those services to cut off the stream when data gets too large for the data type in question. If we didn’t know the data type, these kinds of security choices would be harder. Maximum sizes for an ActivityPub post, for an image, and for a long-form video, are significantly different numbers. A system for hosting posts with ActivityPub may place performance limits at a very different point than YouTube does.

Reference Architecture of Vetted Services

To solve this core usage model, we can now define a pretty obvious architecture using common Internet standards and components.

- Both source and destination services have ways of authenticating the user account and starting authenticated sessions, and they will continue to use those.

- Oauth will be used to check for user authorization. Either the source will initiate transfer and trigger Oauth for the user to authorize the destination, OR the destination will initiate transfer and trigger OAuth for the user to authorize the source.

- Services sending and receiving personal data will use transport security to encrypt all traffic involved.

- Hosts will be identified by domain names and domain certificates.

- Destinations can refuse to accept data that seems to be the wrong type, harmful, exceeds quotas or threatens compliance in any way.

- Destinations that normally host private data will default to incoming data being private.

These architectural components are all pretty common! Most platforms with private personal content already use most of these tools, and certainly host identification and transport encryption are very common. These services already authenticate users and apply content filtering. Most probably have OAuth somewhere in their service architecture, and if not, it’s a mature technology with plenty of libraries available.

To these obvious and well-understood choices, let us add a more surprising one: source servers will vet possible destinations and offer only an allowed list. Destinations may also vet sources and only accept or initiate transfers from their allowed list of sources. (By the way – the choice for source servers to make sure that destinations are acceptable is independent of the choice for authorization to be requested by the source or by the destination. It can work either way).

The choice of vetting other services is a notable architectural choice because it’s a component that the services don’t already have and it may not be trivial to do. It is a weighty responsibility to vet another service and say that it is OK to exchange data with that service, because of the number of bad things bad people try to do with private data. Luckily, for most data types, there’s not too many destinations to consider vetting and listing some top options. If the user wants to move photos, there just aren’t a million or even a thousand photo hosting sites that are reasonable well-known places to host their personal photos. A drop-down list in a Web form, containing a list of vetted photo hosting services, is a reasonable UX choice that covers a lot of user choice, and contains ample opportunity to add new services in the future.

If any of the choices made above are surprising in a bad or disappointing way, remember this is a reference architecture. Especially once we’ve considered the threat model for this reference architecture, we’ll be in a good position to compare what threats are better or worse-handled by a different architecture.

However, now that we’re finally ready to enumerate reasonable threats and how much of a concern they really are, I’m out of time for this week – so that topic will have to wait for another newsletter and another day.