A Threat Model for Data Portability Using a Reference Architecture

In a prior newsletter/blog, I outlined a bunch of requirements and a rough architecture for server-to-server data transfers that are initiated when data owners request transfer. Although many things were left unspecified, enough assumptions have been made to start to talk about what threats exist when doing these kinds of data transfers.

Here’s a quick overview/TL;DR: The threat landscape as it stands today can be broken down into three rough buckets. One is handled primarily by secure communications pathways, including disclosure or loss of privacy and tampering. The second is best handled by ensuring the service providers involved are legitimate and taking reasonable security precautions. And the third is the “more complicated” bucket: harmful content, spoofing, and access control issues. In this piece I’ll explain the overall threat landscape more and dig into the first two buckets in depth, but proper treatment of that big third bucket will unfortunately have to wait for a future post!

Sourcing the threat categories

I came up with a list. Most of the threat types or categories in this list can be found in well-known threat frameworks, particularly STRIDE (security) and LINDDUN (privacy). ITU’s X.800 and X.805 offer security architectures for system interconnection and for end-to-end communication respectively, with many threat considerations framed more positively as “security services” than as threats.

Security Threats involving possessing data/content aren’t always the same as the threats to servers or protocols, so it’s also useful to consult NIST’s catalog (Appendix E) of data threats and Camille François’ Actor-Behavior-Content framework (ABC).

| Threat category | Sources / more info |

|---|---|

| Disclosure of the data being transferred | STRIDE, X.805 |

| Indirect loss of privacy, e.g. linking, identifying, detecting | LINDDUN and NIST |

| Tampering | STRIDE, X.805 |

| Non-Repudiation | X.800 |

| Denial of Service | STRIDE, X.805 |

| Elevation of Privilege | STRIDE |

| Non-Compliance | LINDDUN |

| Harmful Content | ABC |

| Spoofing and related bad actor activity | STRIDE, X.805 |

| Permission and access control challenges | LINDDUN and other themes that arose |

Evaluating each of these threat categories with a high-level architecture to compare against allows for some threat categories to be set aside as mostly solved. Sometimes we can note that more detailed decisions made within the reference architecture can be of further help mitigating threats, and that’s useful as a checklist for future design work.

Some threat types are similar enough to problems that data source and destination services already have to handle that we can use those services’ existing solutions. That’s not to say those solutions are easy (content moderation is very hard!) but they may be routine - the experience and expertise are there to deal with these threats, and the threats can often be handled the same way that they are dealt with when direct user content contributions are involved.

Recapitulation of Reference Architecture

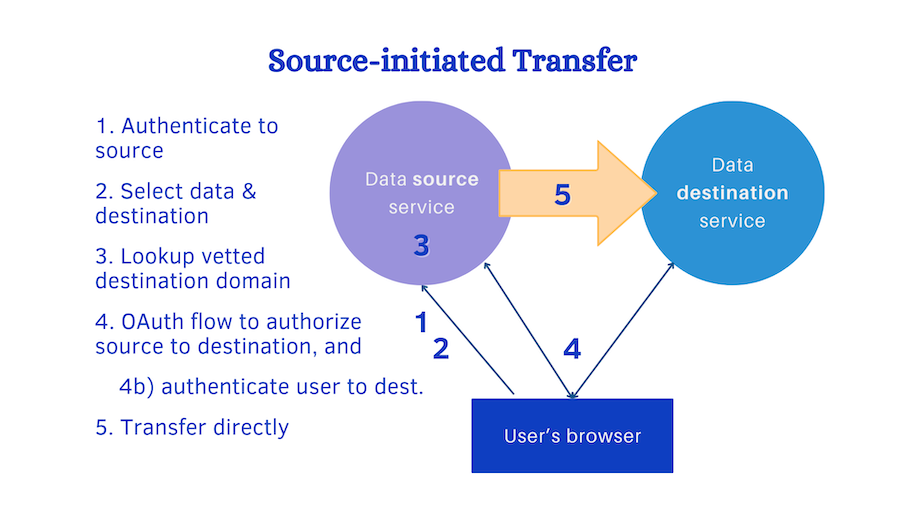

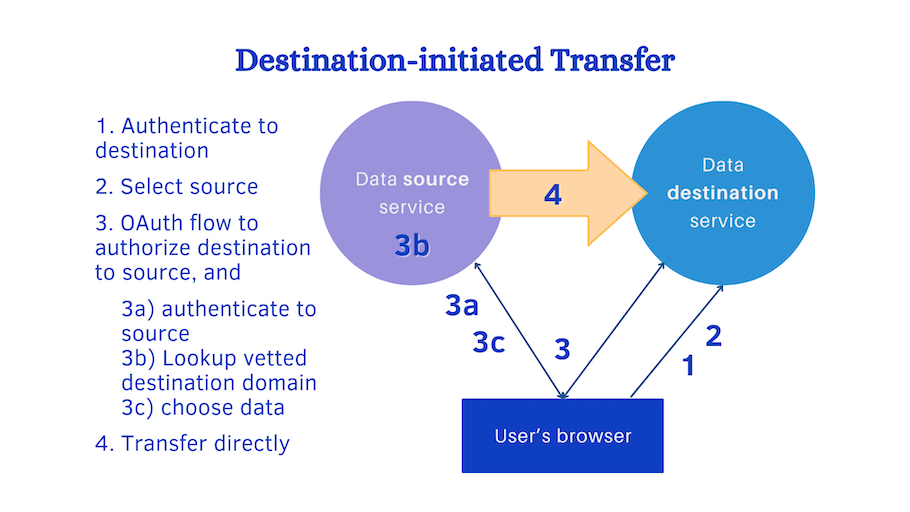

Rather than just refer to the last blog post in this series for the reference architecture, I wanted to briefly re-explain it. The exploration of requirements and scope in that post led to a number of decisions, with one major decision left open: data transfer could be initiated by the source service holding the data or it could be initiated by the destination requesting access to the data. That leads to two very similar architecture diagrams, and two very mirrored sets of steps to start a transfer. One architecture is source-initiated, and the other is destination-initiated.

Both alternatives:

- Use OAuth to authorize one server to the other with the user’s consent;

- Can authenticate the user to both sides;

- Involve vetting the destination service and (if needed) the source;

- Allow the user to use Web pages to choose data and destination; and

- Use secure transport for all interactions.

In source-initiated transfer, illustrated above:

- User authenticates (login, etc) to the source service

- User sets up a data transfer, including choosing what data and what service to send it to.

- Source makes sure that there is a secure domain associated with a vetted destination before continuing.

- a) Source initiates the OAuth flow, resulting in authorizing the two services to each other. b) During this, destination requires authentication (eg. login or session key).

- Data transfer can now begin using a protocol or API over secure transport. The source may use the destination’s API, the destination may use the source’s API, or they may use a standard protocol.

In destination-initiated transfer, second picture:

- User authenticates (login, etc) to the destination service.

- User chooses to load data in from another service.

- Destination initiates OAuth flow, requesting authorization for access to the user’s data. (a) Source requires authentication (login or session key). (b) Source also checks that the destination is in the vetted list. (c) Source also prompts the user to select data to transfer.

- After complete OAuth flow, data transfer can begin, using any API or protocol over secure transport.

Because these approaches both do the data transfer over secure transport, and both allow the source of data to check the destination’s domain against a list of vetted destinations, they both meet the requirements. Actually the destination can add a step to either architecture to do its own vetting of the data source service, if confirming the identity of the source service is necessary in a given use case (see for example data and content threats below).

Using a secure transport helps with threats

If we stipulate that all the interactions in our reference architecture diagrams happen over secure transport, especially the data transfer itself (big arrow), that helps with many threats.

Disclosure or loss of privacy

Much protection from simple exposure of data in transit is prevented by using secure transport. The source and the destination both have access to the data in most cases, but that’s the user’s intent anyway. Secure transport protocols are mature and well-tested, so we can fairly confidently say that this problem can be solved. Of course, the same precautions that are required whenever secure transport is used must be applied. For example, when TLS is used to secure HTTP traffic, the domain certificates of hosts must be checked using well-known steps.

Indirect Loss of Privacy

Linking and identifying are when privacy and confidentiality expectations are violated not by direct access to private information, but by combining other information. For content transfers, we might consider some of the following things confidential:

- The list of contents (album or directory names, data object names)

- The amount of data transferred

- The date and time data was transferred

- The account name, session tokens, etc.

Because the setup of a data transfer happens over secure transport, the selection or filter provided by the user is going to be protected. Then, because the data transfer happens in the cloud, we find we have the excellent property that one user’s data transfer traffic disappears anonymously in the midst of a lot of other traffic.

Many API endpoint addresses and content addresses must be kept confidential to maintain privacy against indirect breaches. Historically this has caused much loss of privacy often with no user visibility into the situation. Whatever protocol/API is chosen for server-to-server traffic, many addresses, labels and identifiers must be secured as well as the content being transferred. This can include URLs for user accounts, URL parameters with user account information or directory names, and other metadata. All these tokens must be secured within the secure transport and not be visible as unencrypted protocol header or envelope data. This is a known principle in using secure transport and many good solutions are known and commonly used.

Tampering

Tampering is quickly dealt with because transport security not only protects the privacy of data being transferred, it also prevents an attacker from modifying the data. It’s important for secure transport to protect the setup also, because we don’t want an attacker to tamper with the setup of the data transfer and try to send the data to a different destination or choose a different selection of data.

If I seem to be waving this off too quickly, wait until I discuss bad actors. I’m interpreting tampering for now as having somebody in the path of transferred data (or the information needed to set up a transfer of data) modifying it en route without authorization, and I’m interpreting other problems as lying within other threat categories.

Vetting source and destination help

Many threats are greatly mitigated by vetting the source of data as well as the destination, depending on the use case. Often it must be both! Services acting as data sources can be harmed by sending data to unverified destinations even if the user requested the transfer. Likewise, services receiving data transfers may be harmed by malicious behavior of unverified sources.

Of course, just verifying a service doesn’t guarantee good behavior, but it goes a long way. There’s no guarantee at all against services “going rogue” - behaving responsibly from one day to the next and building up access and reputation, until one day the service starts behaving maliciously. In the context of data transfers, at least the user is involved in the process. Not only do the source and destination services vet each other, but also the user is actively choosing to send data. Thus, a cautious user could choose not to share data with a service they consider more risky.

Examples where trusting the data partner not to act too maliciously is important, are found within each threat category below.

Non-Repudiation

We can imagine either the source server or the user repudiating some content:

- The user might deny having posted some content to the source; or

- The source might deny that some content was ever posted or deny the timestamp for the post.

This kind of repudiation is mostly dealt with by deciding that the source and destination can vet each other and communicate over secure transport.

This can be important in some cases! A user moving their social media from one server to another might want to set up their account with a history of posts made elsewhere. A post made in 2020 might be moved to a new server in 2023, and we’d like to know if we’re just supposed to take that on faith or if there’s any evidence that it really was originally posted in 2020. The DTI Fediverse Miniconf considered issues like these – why some actors might want to make an account appear several years old when it isn’t, why that’s bad – and discussion can be found in the report.

Non-repudiation turns out to be better solved when direct server-to-server data transfer is used, because the source can believably assert provenance. This is better than when users download unsigned data and upload it to a new destination, where the destination service has no ability to confirm if the user tampered with their own data.

Denial of service (DOS)

DOS threats are already routine for many sites, with or without data transfer functionality. We want to make sure that data transfer doesn’t significantly increase DOS exposure, especially because data portability will result in more data transfer moved more quickly if it’s successful. So let’s break it down a bit:

- Some parts of transfer setup will probably occur using Web pages and forms, and online services already must know how to protect DOS attacks on those.

- OAuth is a widely deployed protocol with a well-known threat model including DOS attack considerations.

- Let’s decide now that it’s OK for services to apply rate throttling or storage quotas to incoming data or data requests.

- It helps that the services can vet each other, if one service throttles to such a low rate that it causes performance problems for the service trying to collate and send data, this can be negotiated between parties.

There are some system design details to setup data transfer to happen gracefully and efficiently (without accidental DOS effects). If a data transfer is set up with the scope communicated in advance, then the destination service knows to expect a large transfer, and can set aside resources or throttle the connection appropriately. If the passive party sends throttling or quota limits in advance, the active party can work within those or notify the user quickly. These details would be good to consider when the data transfer details are worked out, but the high-level architecture already looks pretty promising.

Elevation of privilege

Elevation of Privilege is considered a system security threat that occurs when attackers try to do unexpected things, like overflow buffers, to try to gain access to system resources they otherwise wouldn’t be able to. With this architecture, user interface components and protocol implementations need to have the same protections they would in any other part of the servicers’ user interfaces. Connections to other services, because they are vetted, are at relatively low risk but still good API safety practices should be followed. These protections are all within the power of each service to provide for themselves.

Non-compliance

Non-compliance is a threat when a system that tries to comply with regulations is made non-compliant by participating in data transfer. Any company that has a compliance function already puts controls in place to stay compliant no matter what data users request or upload, so much of this is already in the services’ control.

Many compliance regulations that apply to companies hosting content are driven by the content itself, its subject matter or representation. However, there are additional regulations and policies that are not about what is in the content but how the company handles it.

| Compliance Considerations | Considerations from content itself | Issues in how content is handled |

|---|---|---|

| From regulations |

|

|

| From company policies |

|

|

Compliance overlaps with several other threats. For example, a company can experience a breach that violates privacy expectations and the privacy breach may also cause it to be in violation of regulations or its own security policy or terms of service.

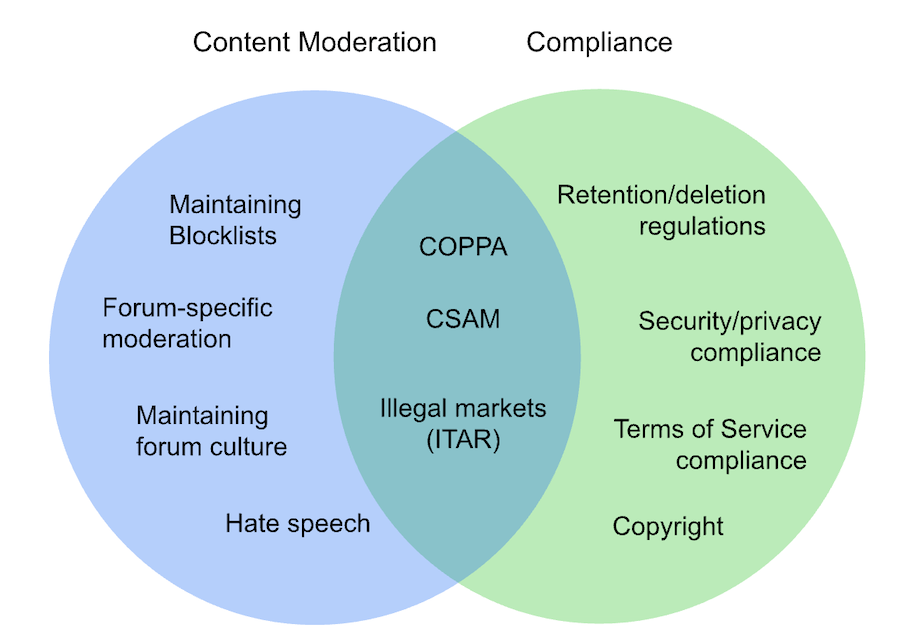

For content hosting services, compliance considerations overlap especially with content moderation, but neither topic encompasses the other:

Lines are blurry but some things overlap more than others

The fact that data is transferred directly between vetted services may make it easier for many companies to ensure compliance. It’s likely that content that is acceptable on one service is also acceptable on another, for starters. The vetting/trusting process for data senders is more than users go through (users may try to circumvent policies or regulations and post content they’re not supposed to) and companies are less likely to get malicious content sent from another service than directly from users.

There are definitely differences between different companies’ definitions of acceptable content and compliant behavior, however. Different jurisdictions, regulations applied to certain industries or services and not others, and different terms of service or privacy policies can all result in a need for the destination to filter content even when it comes from another service.

Most of the work to ensure compliance must be done by each company on their own, for content provided directly from users as well as content provided via other services, so like denial of service and elevation of privilege, we can leave the handling of this threat in implementers’ hands, and the high-level architecture need not change. Low-level features might help, for example providing a content manifest before a data transfer begins, or providing metadata that the content source generated in its analysis of whether the data was acceptable to that service.

The harder threats

Having discussed the threats that are mostly handled by using a modern secure transport:

- Disclosure or loss of privacy

- Indirect loss of privacy

- Tampering

And the threats that are greatly mitigated by vetting service partners:

- Non-repudiation

- Denial of Service

- Elevation of Privilege

- Non-Compliance

I still have three threat categories left that are going to take longer to discuss and I’m leaving for the next blog post.

- Harmful Content

- Spoofing and Bad Actors

- Permission and Access Control

I kind of expected this to telescope into a three-parter blog post once I got started. Any bets on whether I’ll come up with a 4th part before part 3 is out? Stay tuned!