Threat Model Part 3 - Access, Content, and Spoofing

In part one of this series, I defined a reference architecture (or technically, two variations) so that we could evaluate threat models in the context of a proposed system for inter-service transfer of user data. The reference architecture was necessary because defining threat models for all possible systems wasn’t going to be very helpful. Part two evaluated seven classes of threats against this reference architecture. This post will look at the last three classes of threats. I hope the series of posts serves as a reference and explainer, especially as these situations come up in the future:

- When we talk about proposed portability architectures we can compare to the reference architecture and see which threats are better solved with the specific proposal; and

- When we build systems for specific use cases and applications, such as “private photo album transfer”, we can use the ten threat categories explained in the series to thoroughly review the implementation for the specific use case.

So, in this blog post, I dive even deeper into the three threat categories that are extra complicated in content transfer scenarios. They’re all pretty hairy problems with no easy solutions like “sign messages” or “encrypt traffic”.

Harmful Content is already a threat in any system that hosts user-contributed data. It’s especially a problem in bulk, because bulk transfers of data may make it harder or less effective to do content filtering or content moderation, or bypass protections on the more common input channels. Harmful content can be harmful to the service or harmful to other users.

Spoofing is when a data transfer participant tries to convince one or both of the other parties in a data transfer that they are somebody else other than who they are.

Permission and Access are, if not a threat exactly, at least a challenging area to get right and possibly a source of confusion for spoofers to use.

These are nontrivial sources of potential threat. Many can be managed the same way the same threats are managed when content is acquired via existing channels (which is not to say that it’s easy - harmful content for example is widely understood to be a very hard problem already). While the characteristics unique to data portability can pose specific challenges, adding data portability does not appear to break existing protections completely. Much work needs to be done for specific verticals and scenarios.

Harmful Content

While we seem to discuss the threats of data flowing from sites more often than the threats of data flowing to sites, there are threats to both parties. The W3 privacy principles framework puts emphasis on information flows in both directions for consideration of harm.

Bulk Submission

Content that arrives in bulk can bypass normal channels (whatever channels are most commonly used to get content). For example, the normal channel for Instagram posts is one user submits one post at a time via the the Instagram app; and the normal channel for comments is one user submits one comment at a time via the app with a notification to the poster. Normal channels have protections like in-band verifications, notifications (as in the Instagram post/comment example here) and rate limiting.

Many of the common content protection mechanisms are challenging or inappropriate to use in bulk submission, so we’ll list some of these, define and explain the challenge.

| Explanation | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| In-band verifications | There can be verification of submitted content before it is finalized. A user submitting an abnormal media type may be asked to confirm by the Web page. A mobile app may warn that some of the content seems risky to privacy or contains terms that might be offensive before allowing the post. | Bulk content upload/transfer does not allow for in-band verifications like this. Confirmations must be built in differently or skipped. |

| Human Interaction Proofs (e.g. CAPTCHAs) | A special-case of in-band verification is technology that attempts to verify that a human was involved in submitting content or a message. This can be an automated Turing test or a biometric. | Bulk content upload/transfer does not allow for human interaction to be tested at the individual message/post/media level. Bot-generated content can be mixed in with human-generated content. |

| Third-party Notifications | Notification messages can be triggered by content submissions, often for the purpose of immediate review. Many online content platforms send a notification to a content provider when somebody comments on their content. Many forum services notify a moderator so that new content can be reviewed quickly for appropriateness, for meeting terms of service or community guidelines. | Bulk upload/transfer can allow for notifications, but at too high a volume, are likely to be useless or worse. Each message is less likely to be reviewed carefully if it is a large collection of older posts originally posted elsewhere. The flood of expected notifications can hide an important notification of harmful content. |

| Rate-limiting | Rate-limiting and notifications together can work very well to stem a flood of bad traffic. Many social “attacks” involve flooding a comment section, online forum or other venue with messages that one-by-one could be dealt with via notifications and removals. Flooding can be limited in many creative ways, from putting a limit on where a new account can post to limiting the number of comments anybody can submit per comment section. | Bulk upload/transfer must by its nature bypass normal rate-limits, so it will be an attractive channel for bad use in flooding attacks. |

| Quarantine | Sites may quarantine some content submissions; suspicious content may be put in quarantine or all content may go through a step of being visible in a limited way before being published more widely. Email quarantines are frequently used inside corporate and consumer email systems - even if it’s not called “Quarantine”, a spam folder serves a similar purpose. | It may not be feasible to put all or even only suspicious content into quarantine in bulk upload/transfer situations. Processes to move content out of quarantine may not scale to bulk submissions. |

These mechanisms – in-band verifications, human interaction proofs, 3rd-party notifications, rate-limiting and quarantine – cannot be used in bulk transfer situations, or at the very least must be adapted to work a little differently. Thus, content service providers must solve the problems that are solved with these features in a different way for bulk transfer, and that can be a significant effort of new engineering and code/process maintenance. If we consider these mechanisms and challenges while designing data transfer solutions we may be able to help the content platforms replace these mechanisms.

Content Harmful to People

Other researchers and writers have catalogued depressingly the many ways in which content can be harmful to people. Perhaps the best thing to do here is to point to the ABC Framework and the D for Distribution article (which points out that tools that boost distribution can boost harmful content as well as good content). Data portability can certainly be used to boost, change or disguise distribution, so it is worth reading both those articles.

For the purposes of TL;DR: a few examples:

- A user may develop extensive block lists on one social media site but not for another, creating challenges if harmful content is ported between the sites and thus no longer blocked.

- A harasser can use data transfer tools to move their account, again and again and again, to continually evade the block, mute or ignore features of their harassee.

- Disinformation posts can be copied from site to site more easily with data transfer tools. It’s all too easy to imagine a disinformation campaign in which people who support a certain (perhaps extreme) position are asked to copy all of one account’s content into all of their accounts and sites to disseminate that content.

Content Harmful to Services

There are unique risks in bulk-importing data that is normally not imported - data that is normally observed, derived or inferred. Some examples:

- Search engines build logs of past searches that they can use for contextual clues to improve future results.

- Online stores build purchase history databases, then use those to recommend products

- Music streaming services track listening activity to select more tracks to play, as well as to provide info such as Spotify Wrapped.

When these services use activity history to provide benefits to users, there’s a great case to be made to allow the user to bring their own history to a new service rather than start from scratch. However, there are now risks to that new service in importing bulk data. First, the new service needs to be wary of possible tampering that could worsen the service’s functionality (such as importing data claiming that a new song was played ten million times). Second, the new service needs to check the bulk data for buffer overflows and embedded code at least as well as data contributed one-by-one.

E2EE and content safety

What if the content is end-to-end encrypted (E2EE)? In this case, the server is by definition not in possession of keys to unencrypt content. This a situation where content moderation is already challenging.

E2EE is not the most common setup when user-approved server-to-server data transfer is requested, but there are still some potential use cases.

- After using an E2EE messaging app for years, using it to exchange everything from family photos to payment requests, a user wishes to transfer their message history to another service. The messages and photos are all stored encrypted on the original service.

- A digital drop-box service used in the legal industry contains encrypted content submitted by a user (the client), and the keys have been distributed in a different channel to the user’s legal representatives. A client later wants to move this data off the expensive legal site but cannot just get rid of it yet.

To the extent that the interoperability of these use cases can be solved, the use of E2E encryption of content at-rest can make transfers somewhat more risky also. The server that originally stored the encrypted data can make few assurances if it does not hold keys to unencrypt the data; thus in these scenarios we can’t necessarily rely on the source server doing content filtering/moderation. The destination does not necessarily operate under the same model. A service model at the source wherein harmful content detection is done at the client (because of the E2EE design) would present extra challenges when that content is sent to a new destination with a different model to deal with harmful content.

E2EE use cases present a good opportunity to remind ourselves that system models and user expectations can differ significantly between seemingly similar systems. When a personal messaging app that uses E2EE with client storage interoperates with a different personal messaging app that uses E2EE with server-side storage, or a non-E2EE messaging app, data portability can be difficult and even when achieved technically may be done in a way that users did not expect. Practitioners in the area already find that users can be surprised by the results of a data transfer even within the same system (e.g. merging 2 accounts)!

To summarize, the existing challenges of E2EE content moderation are not significantly increased when data transfer is introduced. In specific concrete cases, we do need to be mindful of the safety assumptions on both sides when E2EE content is transferred. Techniques that may allow some identification of harmful encrypted content, such as homomorphic encryption, ought to work just as well in data transfer situations.

Spoofing

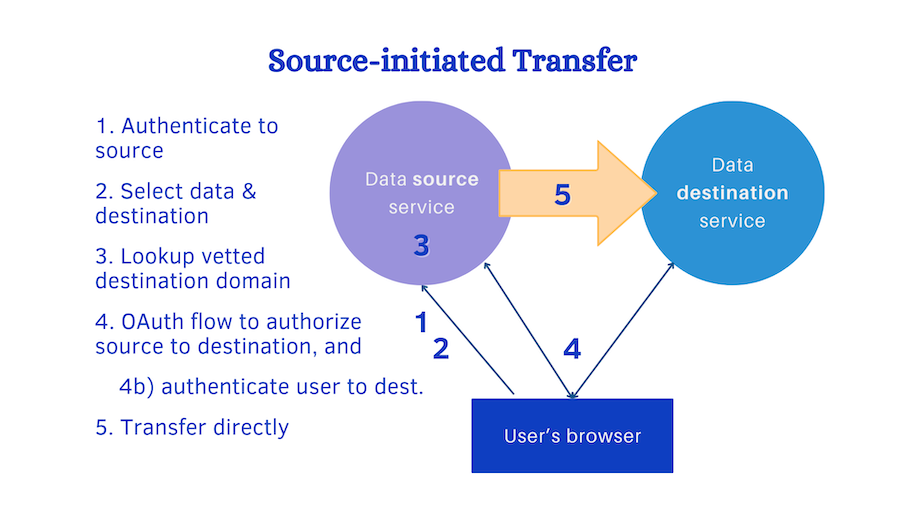

Recall our reference system architecture:

Since this architecture authenticates the user both to the source and then to the destination service, the overall system is well-protected from bad actors impersonating the user. That’s great news, because many threats to services and users come from a small subset of users. It doesn’t make the problem of bad actors go away, but it means that the problem has already been solved by robust systems. A user who attempts to evade restrictions, post harmful content, or otherwise behave in ways that the service provider forbids or prevents, can still be identified in these scenarios, and may often be blocked or removed if their behavior is bad enough.

We also need to make sure that users are protected from bad actors impersonating sources or destinations, and this is a little trickier to see.

New avenues for phishing attacks

The architecture we’ve defined operates on the World Wide Web, and one of the big challenges of the Web is how easy it is to spoof users by pretending to be a legitimate service. For example, an email pretending to be from “photobarrel.com” could actually be from “photcbarrel.com” (with a C where an O should be) and lead to a password challenge; this is an example of both spoofing and phishing. TLS and host certificates do not help here: bad actors can easily obtain certificates too. Data transfer setups may offer new avenues for spoofing, such as:

- A user sets up content transfer from one publishing server to another.

- Because their content is visible on one site then updating on another, an attacker can tell that they have real-time and continuous data transfer in place

- The attacker sends a notification appearing to be the source server sending a regular authentication renewal notification, with links to the attacker site rather than the source site

- The user attempts to quickly authorize the renewal but authorizes something else instead, or their password is phished.

While there are undoubtedly new avenues like this, spoofing and phishing are already so common that we need mechanisms like two-factor authentication and authentication challenges whenever the stakes are high. Practitioners in the area have seen verified instances of data exfiltration attempts and successes using data portability tools.

Vetting services

A significant protection we can employ to protect users from these attacks is to limit data transfers to happen between pairs of vetted, known participants. DTI is working on ways to standardize a trust model (recently announced!) so that decisions to trust sources and destinations can be more accountable and transparent.

What does vetting data transfer partners solve? It prevents the worst opportunities for spoofing, because a user fooled by a visual URL scam like “photcbarrel.com” will not be able to use that domain name in the data source service without that service being able to tell it’s not vetted. It’s also possible that the user will only select from a list of available destinations.

Some data transfer use cases can allow unvetted participants more safely, but in the cases where risks are higher, trust between services is important and feasible, and the challenges to scale N-to-N trust can be addressed.

Permission and Access challenges

One of the greatest challenges remaining in doing data transfers with appropriate privacy isn’t even caused by bad actors - it lies in the difficulty of translating a vague user intent into detailed software algorithms.

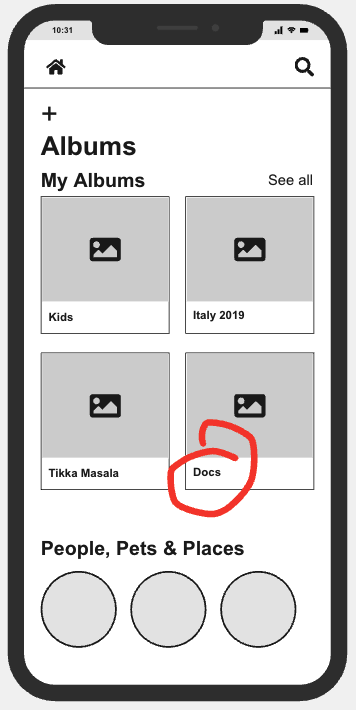

Photos once again provide a simple example of this. I may have many photos on a service, especially if that service collects photos automatically from my devices and conveniently stores them in one place.

It’s all too easy for a photo migration project to include images I don’t even think of as photos: that picture I took of my driver’s license, or a screenshot of some HR data or scan of financial documents. Ideally the source of a data transfer would be able to check on the situation and help apply appropriate filters. To that end, it would help for the source to know some of the context for the destination, such as whether the transfer will result in publicly accessible content. This is an interesting feature to design for, and very content-dependent.

We also have permission and access challenges with the destination. Many services accepting user data would like to know the user intent when accepting it. You’re uploading a photo, would you like it to be private or public? Would you like it to be Creative Commons licensed or copyright protected? Which folders? Which tags? Would you like it to go on your stream? If a new playlist is uploaded, should it be added to the user’s playlists? Should music not yet purchased be purchased now? What if quota is exceeded, do you want to pay for more quota now?

Just like any complicated activity can go badly, and the results can be mistakes from the user point of view, complicated data transfers can be done badly. Even with legitimate source, destination and authorized user, no attacks or bad actors in sight, a user can accidentally copy a photo album of docs to a public location. Phrased as an accident, it’s not technically a threat – but sometimes bad actors set up victims to make mistakes. A site requesting photos for “cancer research fundraising PR purposes” or another benevolent goal can induce users to share more than they intended. We need legitimate data transfer hosts and destinations to present carefully designed and tested User Experience (UX), and in some cases we need extra information during transfer setup so that the source can learn more about the destination and vice versa.

We can talk about architectures that involve detailed setup on both sides - careful filtering of content on the source side, thoughtful application of privileges and licenses on the destination side, or other choices that these services find important depending on their context. Maybe the solutions will involve more complicated use of OAuth, or more handshakes between the services to make sure both sides have completed checking with the user how they want this to work.

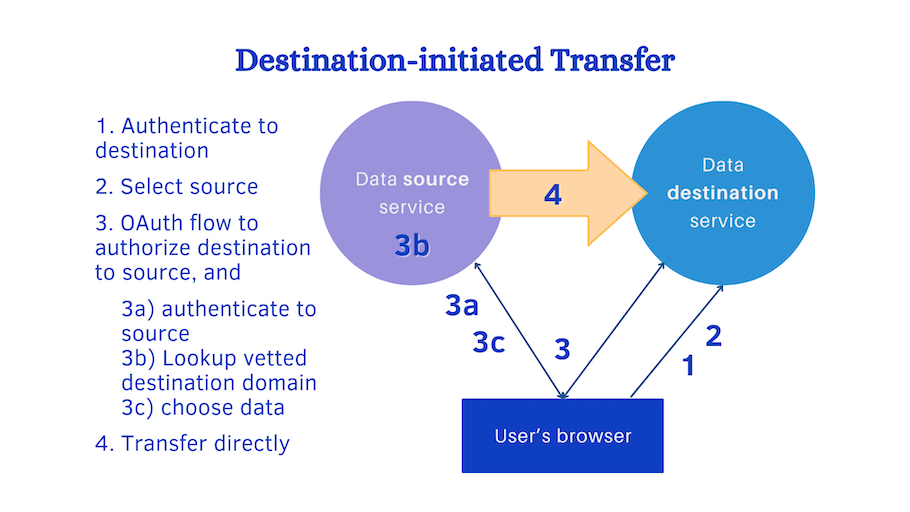

Who initiates

We illustrated the authentication issue with the source-initiated architecture. Is it any better or worse in destination-initiated transfer? When the source service initiates transfer, whether it be in an app or a Web page, the source can supply all kinds of UX, including selections, verifications and filters, to make sure that the correct limitations are used to generate outgoing data.

In contrast, in the architecture where the destination initiates transfer, the destination (an app or a Web page) can show all kinds of UX to ensure that when the data arrives, the correct permissions and licenses are applied to the incoming data.

Since both parties need to present these decisions in a clear informative UX, we need solutions that allow both.

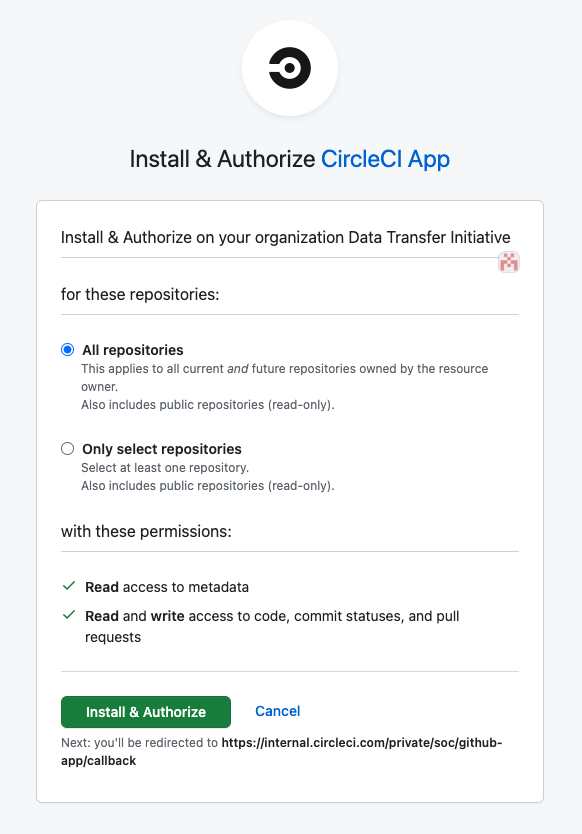

Our choice of OAuth for the way that users authorize second service is key to this dilemma. Not only is it a good interoperable choice for authorizing the user, it also allows the responding service to include any number of decision-making steps in Web pages in the path of authorizing transfer. It doesn’t make all the problems easy, but it is a pretty powerful framework.

When CircleCI initiates an OAuth interaction with GitHub, GitHub’s interstitial Web page asks about scope and permissions in a clear way

Post-transfer permission and access work

Consider the use case where there are detailed dispositions to be made after a content contribution.

-

Flickr has a sophisticated upload UX, with the ability to choose tags and albums for some or all photos in the upload, and to consider which photos should be private, public, limited to family, and/or Creative Commons licensed.

-

Wikimedia Commons has a contributor flow that involves long Web forms for several of the steps in their flow.

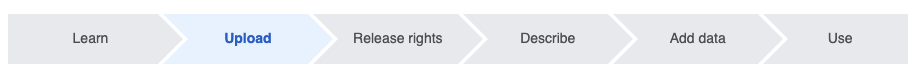

Wikimedia contributor flow: Learn, Upload, Release rights, Describe, Add data, Use

The interesting thing about their UX is that it happens after the data upload is complete – both Flickr and Wikimedia Commons show thumbnails of the images so that users know exactly what they’re annotating and are less likely to make mistakes. If we architect data transfer such that it happens out-of-band with the user, it could be more challenging to apply the right privacy choices on the destination. This is another area where data transfer participants will have to be thoughtful and innovative in designing UX that helps users make good choices and fewer mistakes.

Summary

In this third part of the three-part threat model blog post series, we got deep into some threats that are highly detailed and depend deeply on use cases, context, and human interaction. Harmful content, spoofing, and permission challenges are all threats already to sites that host content publicly or privately, and data transfer might at times complicate those threats.

In the entire series, we established a core usage model and a reference architecture, then proceeded to analyze threats. Even with a few variations, the reference architecture has allowed us to build a reasonable threat model and offer some reasonable mitigations.

Significant changes to our assumptions may require additional threat analysis. Specific solutions also require detailed threat analysis of the characteristics and interactions of that solution. It’s not an intractable problem, however, or at least no more intractable than the challenges that content platforms already face.